Loom - Part 1 - It's all about Scheduling

The first problem with concurrency (and computer science in general), is that we're extremely bad at naming things. We sometimes use the same word to describe several distinct concepts, different words to describe one and only thing or even different words to describe different things but swap meanings depending on context!

Part 1 in a series of articles about Project Loom.

In this part we skim the surface of scheduling history before diving into the JVM.

The companion code repository is at arnaudbos/untangled

If you'd like you could head over to

Part 0 - Rationale

Part 1 - It's all about Scheduling (this page)

Part 2 - Blocking code

Part 3 - Asynchronous code > Part 4 - Non-thread-blocking async I/O

There's only one hard problem

To make sure we're on the same page, let's read what Wikipedia has to say (as of today) about Light-Weight Processes:

In some operating systems there is no separate LWP (Ed.: Light-Weight Process) layer between kernel threads and user threads.

This means that user threads are implemented directly on top of kernel threads.

In those contexts, the term "light-weight process" typically refers to kernel threads and the term "threads" can

refer to user threads.

On Linux, user threads are implemented by allowing certain processes to share resources, which sometimes leads

to these processes to be called "light weight processes".

Similarly, in SunOS version 4 onwards (prior to Solaris) "light weight process" referred to user threads.

— from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Light-weight_process (emphasis mine)I find that confusing to say the least, especially from an application developers' point of view: I'm not that very interested in knowing the implementation differences between operating systems past and present (Unix System V, SunOS, really?).

Let me drop a few terms in a conspicuous attempt to show off:

- Process

- Lightweight Process

- Thread

- Lightweight Thread

- Kernel Thread

- User Thread

- Green Thread

- Fiber

- Knot

- Goroutine/Coroutine

- Async/await

Quick questions:

- Can you spot the mistake?

- Do you know what concept each of those terms refer to?

If you've answered twice, stop reading and go do something else!

Still with me? Alright let's try to untangle this by first taking a look back in history.

The Land Before Time

Sequential execution

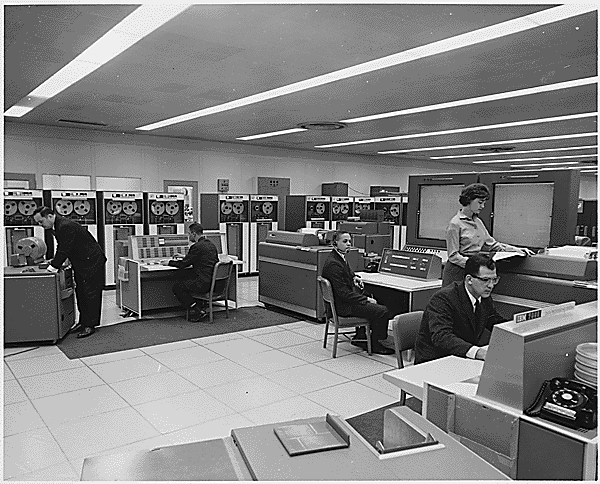

The first computers were capable of running one set of instructions, a program, sequentially and would sit idle the rest of the time. Up until another program was executed. Kind of like a sewing machine (or a loom!).

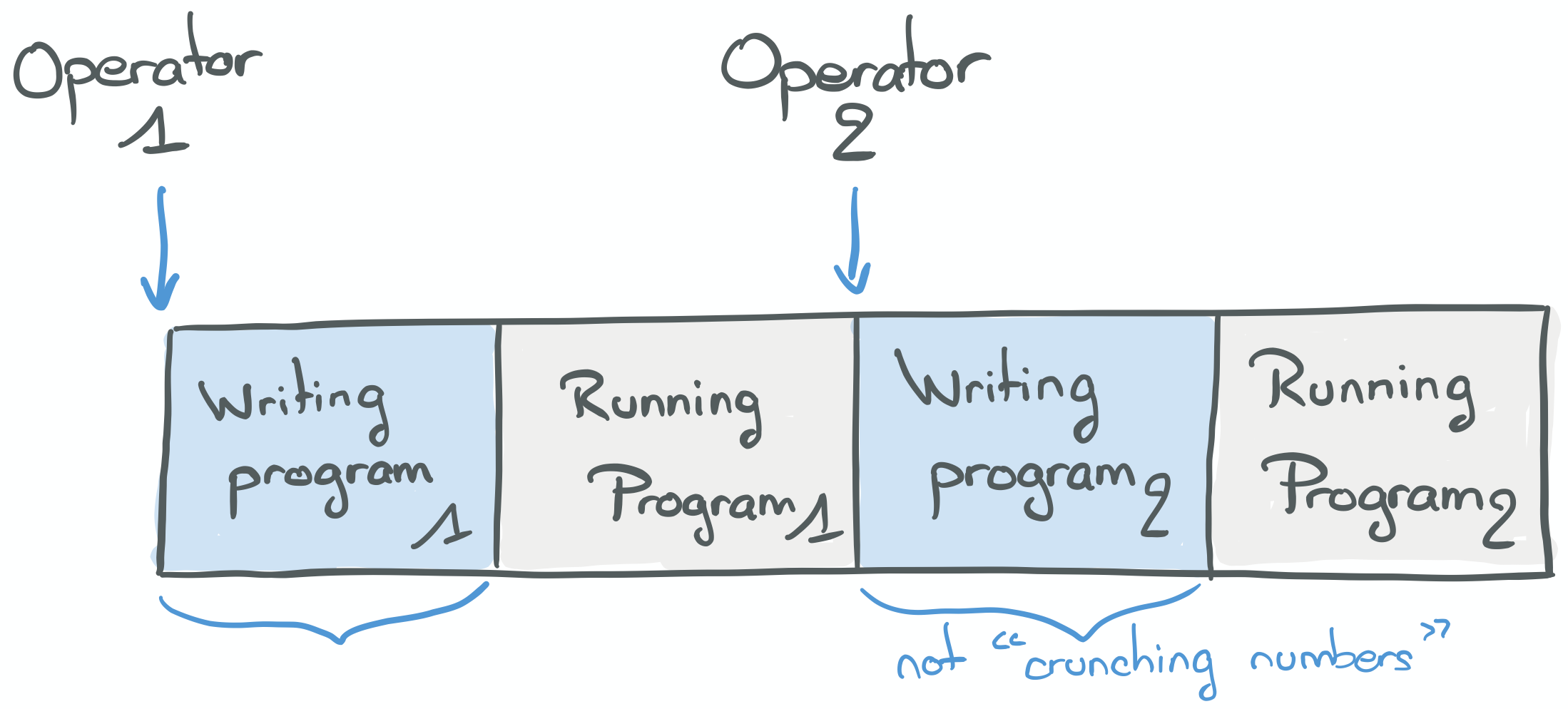

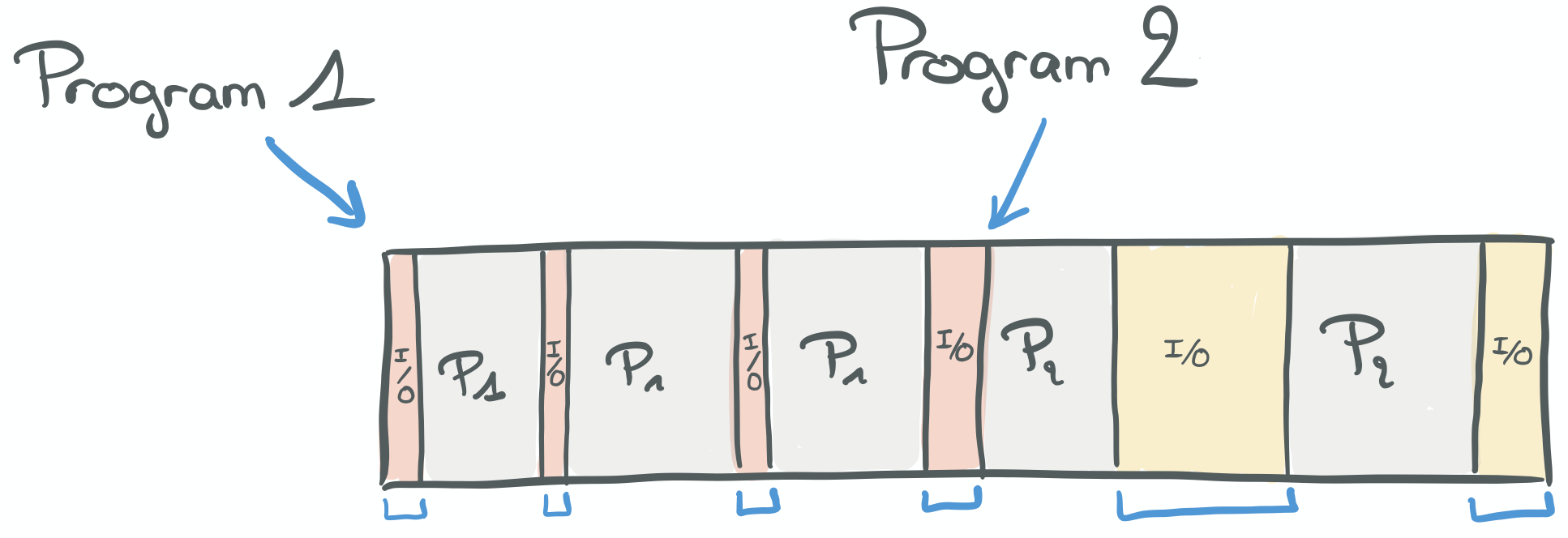

The diagram below shows the execution of two distinct programs on such a computing machine.

"Operators" were the names of the first computers, who used computers.We have two operators. The first starts "writing a program" (wiring cables, turning switches, etc) to make the computer compute the solution to a problem.

Operator 1 must wait the end of the program to get the result. Only then can Operator 2 write her program and make it run. There is no possibility for parallelism: the programs are executed sequentially.

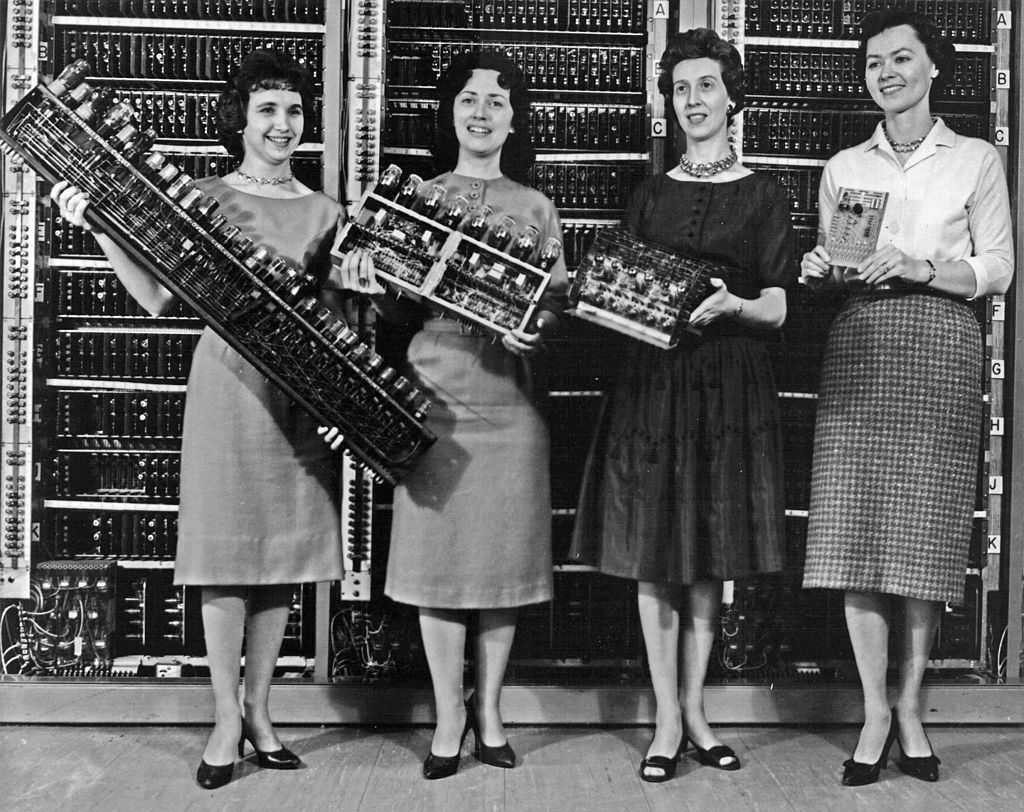

Soon, the bottleneck to solve problems faster shifted from computers to humans. Indeed, even with new ways to write programs (punch cards, magnetic tapes) the time taken by each programmer to "insert" its program into the machine became unacceptable—i.e., too expensive.

In this situation, a good scheduler has to do something. Right?

Batch processing

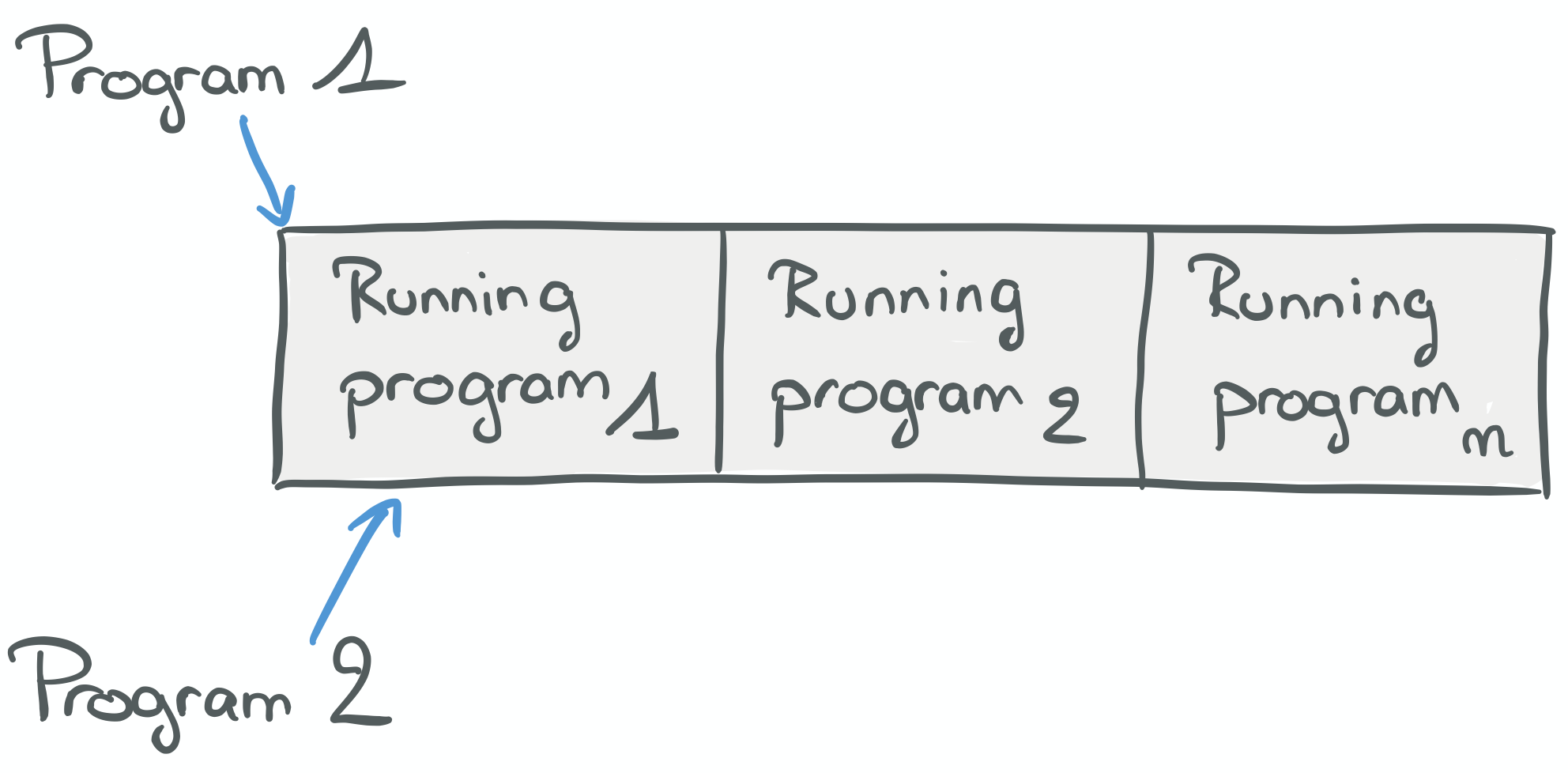

In this case, the schedulers were computer scientists and manufacturers. They came up with this really sensible idea that, to amortize the cost of running many jobs sequentially, one could "batch" them.

Not only let programmers write program instructions on their own, away from the machine, but let them "offer" their programs to a waiting queue of jobs to be performed.

In the diagram above, Program1 and Program2 are submitted one after the other, so Program1 runs first and thenProgram2.

But having to append a program into a "giant" batch of jobs for the mainframe to compute, and then wait for it to return all the results, was a massive pain in the butt! Imagine debugging your programs with a 24 hours feedback loop...

{{< image center="true" src="https://i-rant.arnaudbos.com/img/loom/kropotchev.png" title=""Batch processing" spoof movie — Stanford" alt="Silent spoof movie relating the adventures of a programmer waiting on batch processing." width="50%" link="https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/punched-cards/2/211/2253">}}

It was not only painful for programmers though. It was also painful for users who would have to run the programs!

It's a common problem in scheduling: optimising for a use case (less computer idle time) ends up making it worse from another point of view (more human idle time).

Computers kept getting faster and faster for sure, and although programmers tried to make the best of the computing power they could get, any single user wouldn't make efficient use of a computer by herself!

Indeed, processes, to do something useful, have to be fed with inputs and produce any kind of output. Otherwise they'd just be raising the temperature of the room. Consuming inputs today can be reading from a keyboard, hard drive or network card. In the sixties, it mostly meant reading from magnetic tape or a teletypewriter. Similarly, producing output meant writing to magnetic tape, printing to a teletypewriter or a "high-speed" Xerox printer.

In the above diagram, we can see Program1 finishing before Program2 can start, but there are gaps between bursts of execution. Same for Program2. So all the time during which a processor is waiting for I/O (polling, busy waiting) rather than "crunching numbers", is wasted.

Schedulers to the rescue!

Time-sharing

The video below is a gem.

In it, you can see Turing Award winner Buddy Holly Fernando Corbató explain the promises and premises of time-sharing as it was being designed.

Processes wouldn't spin on I/O anymore but rather be parked, while another process would be allocated CPU time. Time-sharing allows concurrency: the illusion of parallelism and efficient use of physical resources.

Let's see an example:

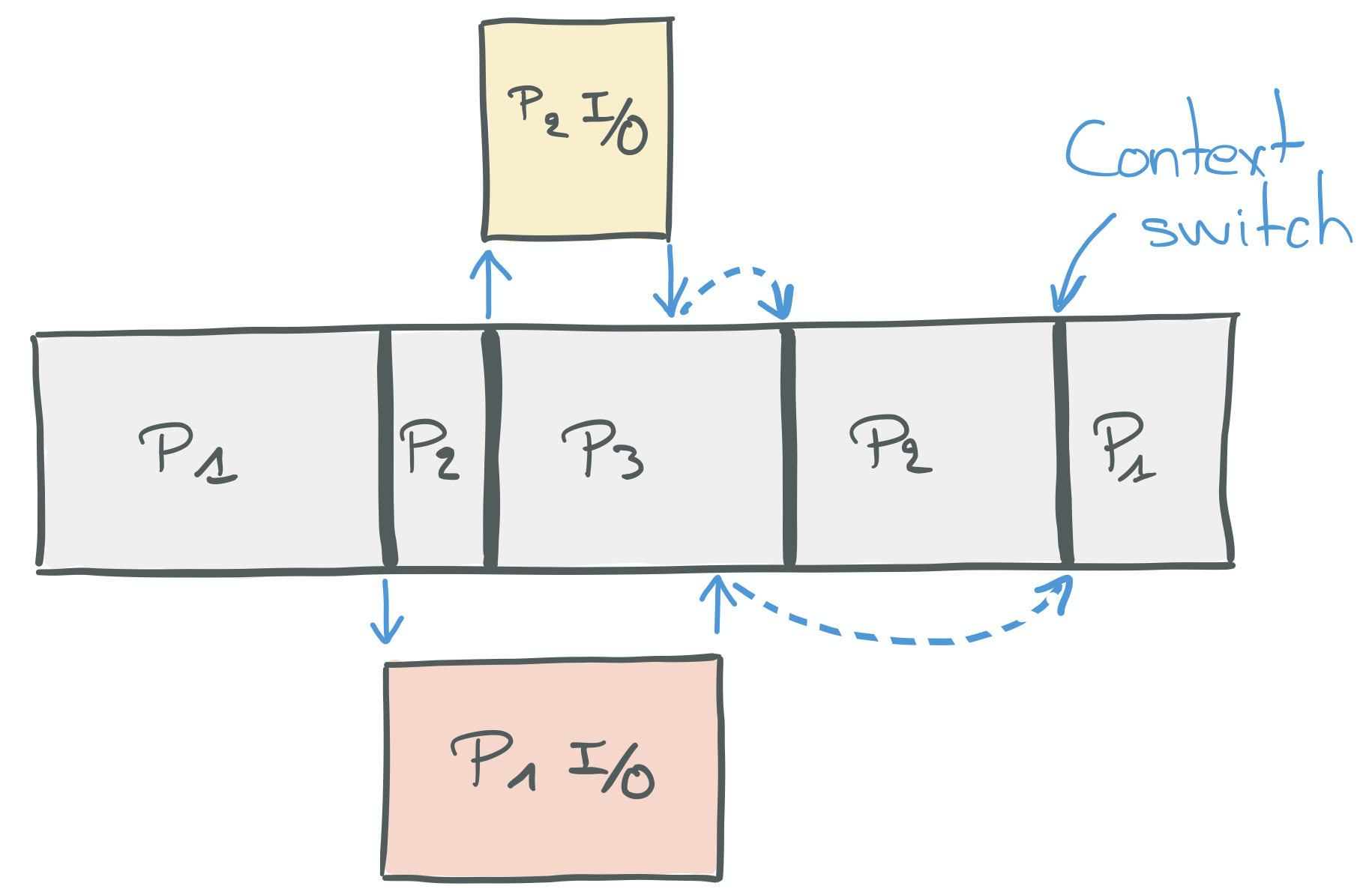

In this diagram, Program1 starts first and is parked when it starts a blocking I/O call. Program2 then gets a chance to run but is quickly parked too as it also makes a blocking I/O call. Some other program, Program3, runs while 1 and 2 are parked. Program2's I/O returns first, so on the next shift, Program2 is unparked and continues to run while Program1's I/O returns. Program2 ends eventually. Program1 then picks up the result from its I/O call and finishes running too.

Process switch

In the previous sections I've considered all programs equals, but as always, "It depends".

P1, P2, P3 could very well have different subroutines lengths but also very different characteristics with regard

to the kind of work they do.

CPU-bound tasks that don't require much (if any) communication could be tackled by multiple processes (instances of a program communicating through IPC).

Some other tasks require communication. Coupled cooperative processes for which IPC may be too expensive are an example.

Tasks requiring many I/O operations (I/O bound) as well.

For such applications, the time to switch from e.g. P1 to P2 and back to P1, may hamper its fast realization

and/or drain physical resources...

From a scheduling perspective, it would be nice to have a mechanism so that cooperative processes (of which there were more and more) could communicate without being taxed by "expensive" communication mechanisms. Similarly, it would be nice to have a mechanism so that I/O bound processes wouldn't undergo excessively costly process switches.

A process switch is a special case of context switch applied to processes.

As the name may suggest, it is a special mechanism for kernels to switch a process by another to achieve concurrency.

As usual with names, "context switch" is overloaded, and we'll mention this in the next sections.That's how threads got introduced: nowadays the most widespread fundamental unit of concurrency is not the process, it's the thread. And threads have interesting characteristics with regard to the previous points.

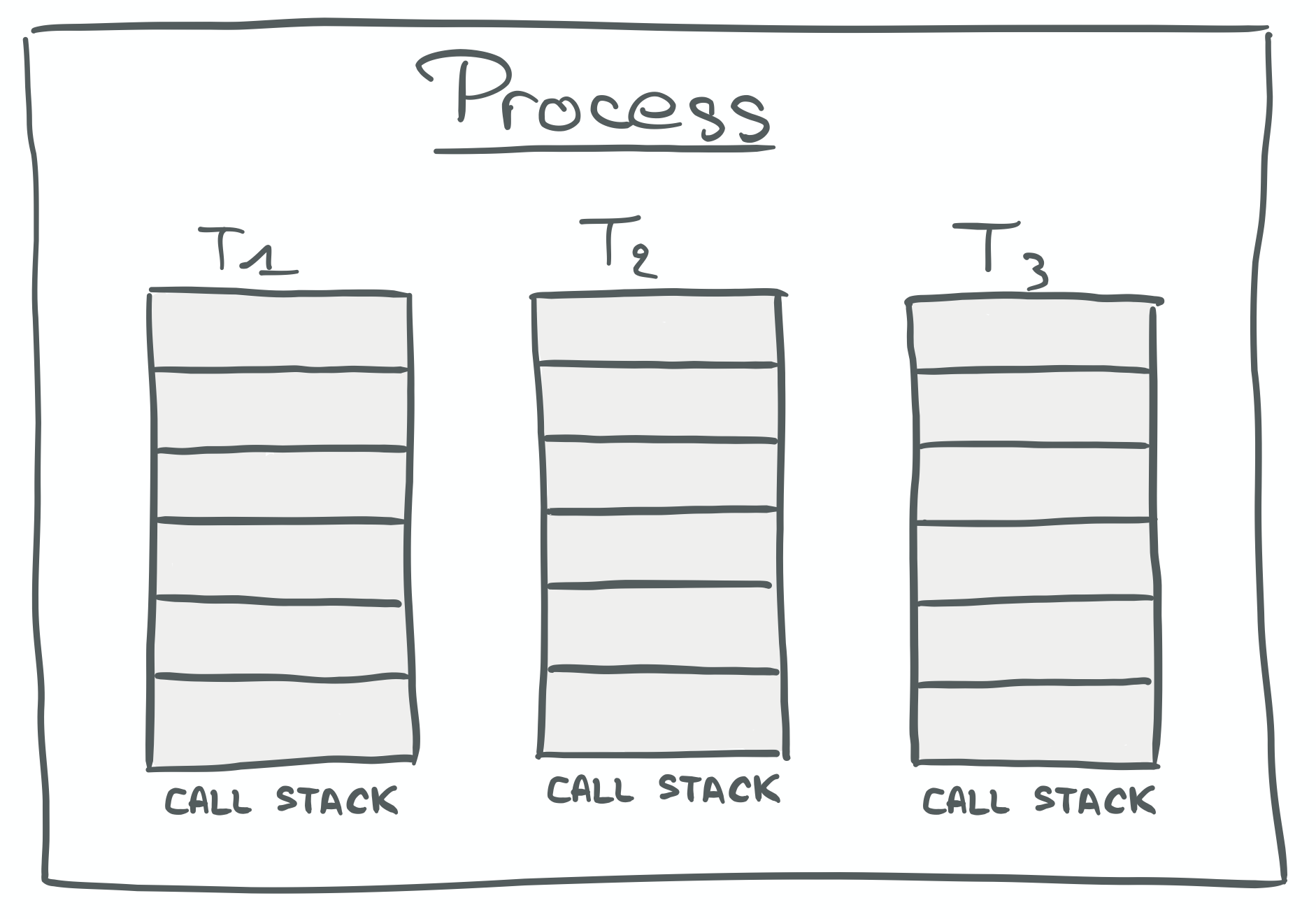

Threads

Conceptually, a thread is like a process: it embodies the execution of a set of instructions and, at runtime, gets its own control stack filled with stack frames. What's really remarkable about threads however, is their ability (for better or worse) to share the memory of their parent process.

Each thread having its own call stack makes it possible for multiple threads, while in a single process, to execute different sets of instructions running in parallel on distinct cores.

Therefore, cooperative processes can be implemented as a single process, with multiple threads communicating directly by sharing memory places (data).

I/O bound processes also benefit from this new layer of indirection because switching between threads of the same process is typically faster than switching between processes.

Nowadays, a context switch is almost synonymous with switching between threads rather than between processes.

But "context switch" is also used, in many blog posts and articles, to talk about process switches,

thread switches or mode switches, almost indistinguishably.

We'll touch on these differences in the next part.Let's talk about time-sharing a bit more.

Multitasking

Time-sharing gained traction after the realization that computers had become powerful enough to be under-utilized by their users and that connecting more users to one would amortize its cost.

In order to do that, time-sharing employed both

- multiprogramming: multiple programs running concurrently; and

- multitasking: programs would run one after the other, in short bursts (preventing greedy programs to monopolize the CPU).

There are several techniques that can lead to effective multitasking and fair (or not) sharing of CPU cycles, but they

can be grouped in two main categories: Preemptive multitasking and Cooperative multitasking; and their properties are

enforced by scheduler policies.

Preemptive scheduling

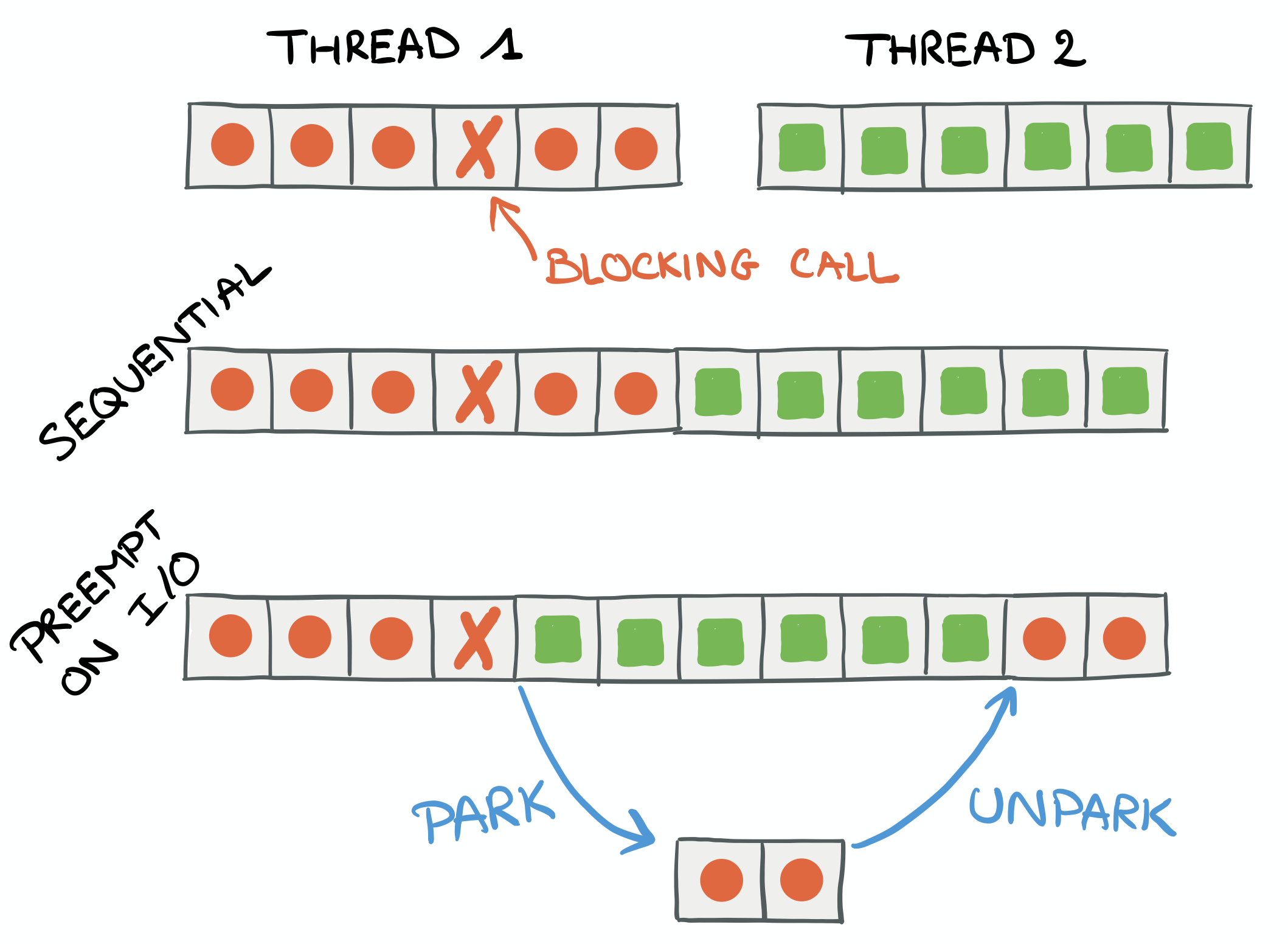

A preemptive scheduler may suspend a running thread when it blocks on I/O or waits on a condition, so the processor can be assigned another thread to work on. It may also prevent spin-locking or CPU intensive tasks to hog the CPU by allowing threads for a finite amount of time, before parking them in order to let other tasks a "fair" chance to run.

To be fair (pun intended), "fair" scheduling isn't a solved problem, and I didn't dive into the details of the

algorithms. These two resources may be good entry-points for more research Completely Fair Scheduler and

Brain Fuck Scheduler.

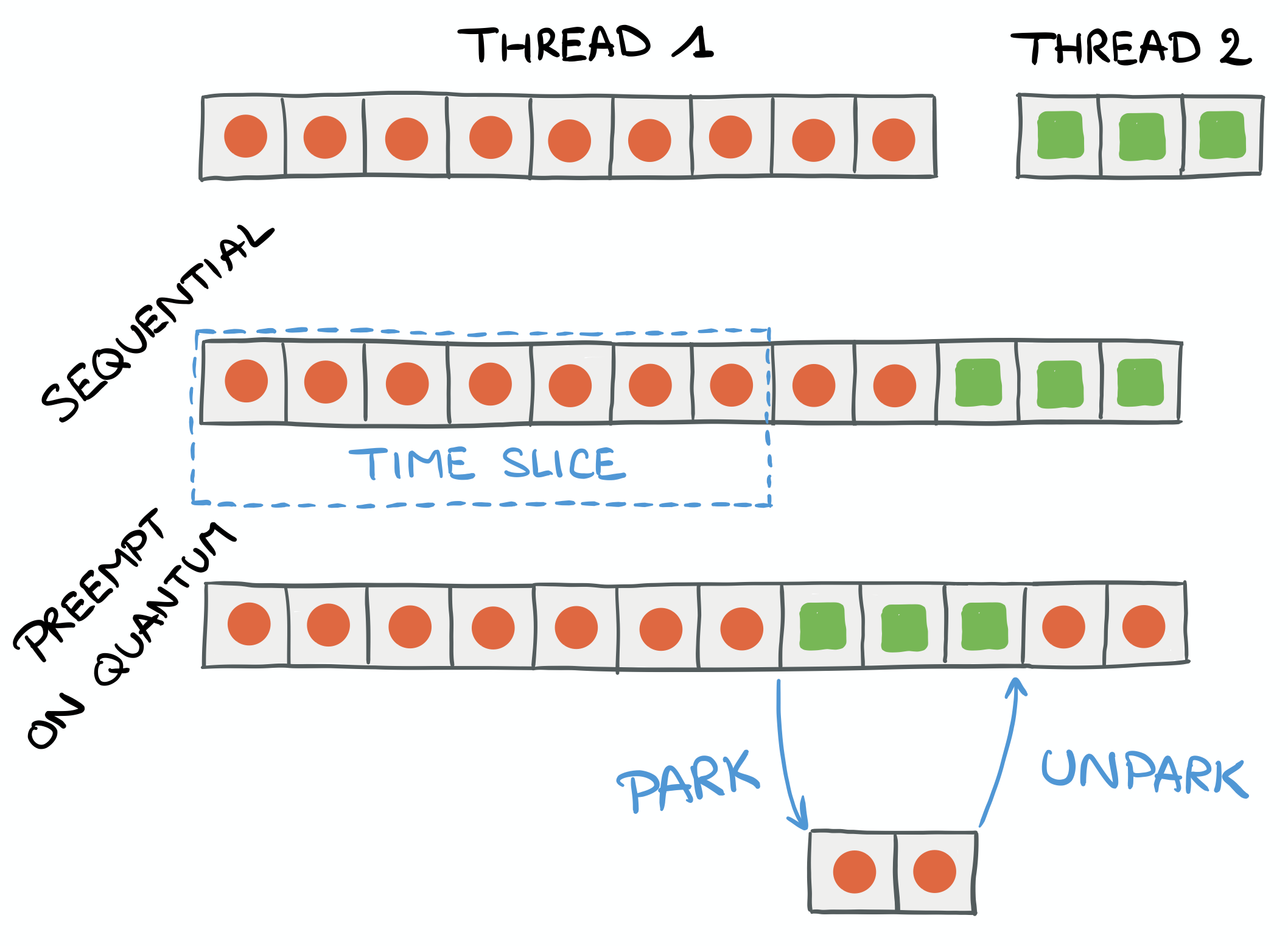

The first figure (left) illustrates a thread/task being preempted by the kernel, using a context-switch when a blocking call occurs, in order to satisfy the scheduling policy: the first thread is parked while the next thread is executed. Eventually (hopefully), the first thread is going to be unparked and its execution resumed.

The second figure (right) illustrates a thread being preempted because its execution duration is longer than the time it is authorized to run on the CPU (also named its quantum).

Preemptive multitasking is what we get from our modern operating systems, or kernels. The preemption is specified inside the kernel scheduler's algorithm.

Cooperative scheduling

Cooperative multitasking, also known as non-preemptive multitasking, is a style of computer multitasking in which

the operating system never initiates a context switch from a running process to another process. Instead,

processes voluntarily yield control periodically or when idle or logically blocked in order to enable multiple

applications to be run concurrently. This type of multitasking is called "cooperative" because all programs must

cooperate for the entire scheduling scheme to work.

— From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cooperative_multitasking (emphasis mine)

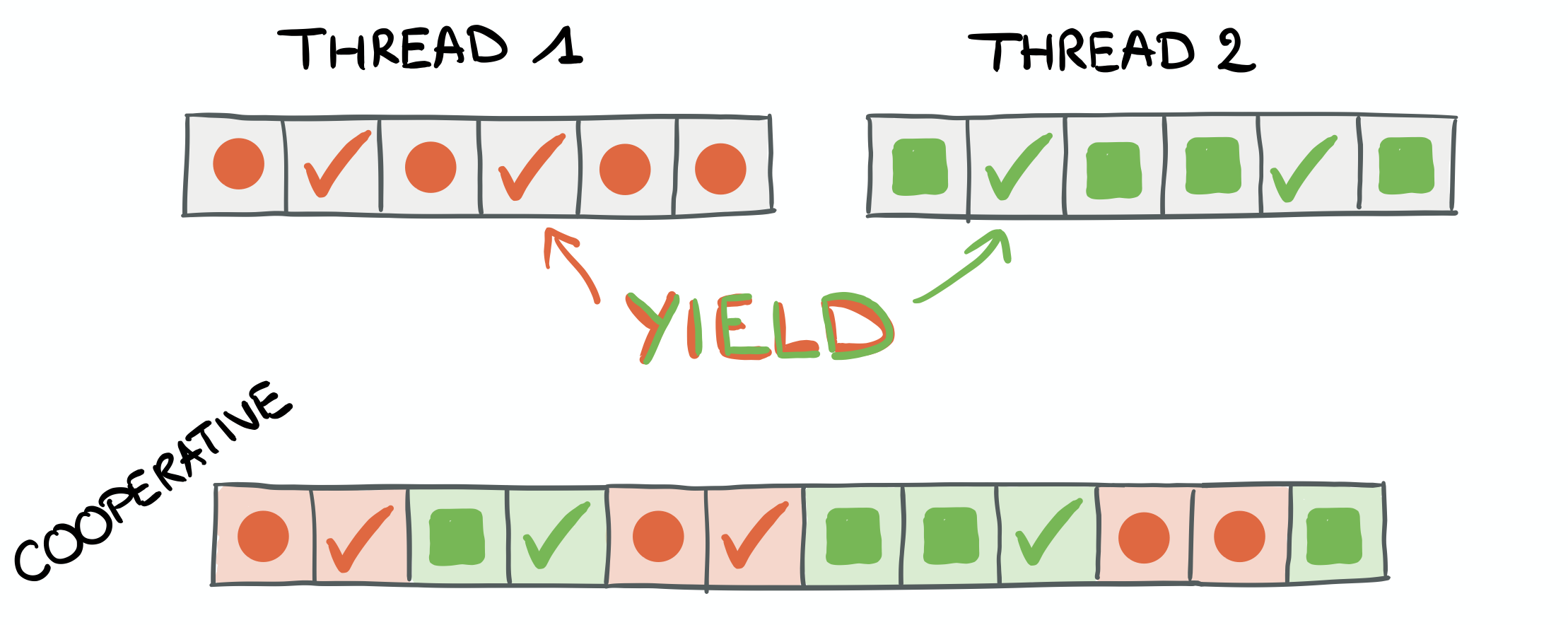

In the diagram above we can see two threads. Both containing interleaved "random" instructions

(any code that this thread is supposed to run) and yield statements.

With cooperative scheduling, there is no intervention from the kernel to pause a thread and schedule the next one. This is all done by each task, deliberately relinquishing CPU time when it is not using computing resources (e.g. waiting on I/O after an asynchronous call).

Cooperative multitasking requires ALL programs to cooperate. Consequently, fairness is not ensured, which explains why most modern operating systems implement preemptive scheduling.

To be continued

I think we've covered most of the groundwork necessary to understand where we're at, from a scheduling point of view, regarding modern computers.

I obviously took a great detour to explain some fundamentals. There's been so much innovation in computer systems in the last 60 years that I had to cut corners and didn't do it any justice.

If it picked your curiosity, start with the links I've provided and follow those threads (pun intended).

Alternatively, this Twitter thread covers about the same period but with more details (dates, pre-historic computer names, etc):

OK SO let's say it's 1962 and you're lucky enough to be a programmer working somewhere that has an IBM 7090. This is a top of the line transistorized revision of the IBM 709, capable of 100,000 floating point operations per second. But how do you code for it?

In the next part, we will experiment!